The Wars of the Roses

An aftermath of the Hundred Years War.

The long dynastic struggle that would much later come to be known as the "Wars of the Roses" (1455-1487) had its roots far back in the Hundred Years' War. Edward III had five sons, most of whom not only gained experience as military leaders during the war in France but also amassed great wealth. The official heir was Edward III's eldest son, who became famous posthumously as the "Black Prince", but since he died before his father, in 1377 the crown passed to his four year old son Richard II, for whom his uncle John of Gaunt led the regency. When Richard had come of age and was himself reigning, conflicts with the nobility became

more and more frequent. The great magnates in particular, who jealously guarded their newly

gained independence, rallied under the leadership of John of Gaunt and his son Henry the

Duke of Lancaster, who finally managed to depose Richard and crowned himself as Henry IV,

thus initiating the reign of the house of Lancaster. In the following years, he had to put

down some rebellions, but was able nonetheless to consolidate his power so that his son and

successor, Henry V (1413-1422), could resume the war with France soon after succeeding the

throne.

When Richard had come of age and was himself reigning, conflicts with the nobility became

more and more frequent. The great magnates in particular, who jealously guarded their newly

gained independence, rallied under the leadership of John of Gaunt and his son Henry the

Duke of Lancaster, who finally managed to depose Richard and crowned himself as Henry IV,

thus initiating the reign of the house of Lancaster. In the following years, he had to put

down some rebellions, but was able nonetheless to consolidate his power so that his son and

successor, Henry V (1413-1422), could resume the war with France soon after succeeding the

throne.

Henry V achieved a spectacular victory at Agincourt in 1415, after which he formed an alliance with Burgundy and in the end controlled large parts of France. Nevertheless, he had gravely overestimated the capabilities of the English, and the limited resources assigned were far from sufficient to fund the necessary forces for a long time. The first setbacks appeared when France began to professionalise her army, which led to severe defeats when Burgundy made a separate peace with the French.

Only the desolate state of the heavily devastated France delayed the war's end. But when fighting reassumed after a prolonged cease-fire in 1449, within two short years the English lost nearly all their old possessions in Normandy and Guyenne.

Many historians consider the masses of defeated mercenaries returning from France to be one of the main causes of the Wars of the Roses. There had undoubtedly been dynastic conflicts in England before, but apart from the long feud between Queen Matilda and Stephen of Blois, there had never been such an enduring and bitter struggle for the English throne. The unemployed veterans of the Hundred Years War were the ideal reservoir for anybody looking for experienced and ruthless fighters. In addition, in recent decades the English had settled many colonists in Normandy, and these were now also returning having lost everything.

Even more dangerous were the struggles of the great magnates, trying to control the increasingly insane King Henry VI. The war in France had long served as a valve allowing the power-hungry nobles to expend some of their pent-up energy. The most dangerous contender for power, for example, Richard Duke of York - also a descendant of Edward III and thus a Plantagenet - had served several times as a commander in France. After the final English defeat at Castillon (1453) the nobility focused their energies on the struggle for power at court, many of them looking for compensation for lost estates in France.

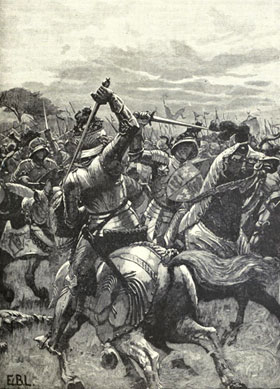

At first Richard of York succeeded in prevailing against the faction around Queen Margaret and was accepted as regent. But when the king recovered enough so that Richard was ousted from office, open war broke out with the first Battle of St Albans in 1455. The course of war was changeable, repeatedly interrupted by long truces and various attempts to reach an agreement by negotiation. In 1460 Richard of York fell in the battle of Wakefield and was succeeded by his son Edward, who was victorious a year later at Mortimer's Cross and then had himself crowned king as Edward IV. In 1461 he crushed the Lancaster faction at Towton, forcing their last partisans into exile in France.

Of course, many of the English archers and men-at-arms could be called mercenaries because they fought for whoever paid them. The pay, at six pence a day for an archer and twelve for a man-at-arms, was a good deal more than the earnings of a craftsman and certainly therefore a key factor for many hungry veterans. However, most men followed their feudal lords, albeit with good pay, and were dependant on the regional partisans of Lancaster or York. Because of this a greater understanding can be reached by focusing on foreigners while investigating the role of mercenaries. In this regard the Wars of the Roses looked like an inverted continuation of the Hundred Years' War, because Lancaster sought French support, while York aligned itself with Burgundy.

Initially both parties had little reason to recruit from abroad because England was full

of unemployed former soldiers. Only when it came to the relatively new firearms had England

considerable unfulfilled demand. Artillery had already proven its importance in the final

phase of the Hundred Years' War, especially during sieges, but also increasingly in battle.

Though there were gun founders and gunners in England, they were nowhere near the quality of

the those of the French and Burgundians. The first "handgonners" equipped with portable

firearms seemed to have been exclusively foreigners. Despite the fact that there were thousands

of experienced archers available, many commanders - all seasoned veterans who knew what they

were doing - spent increasingly large amounts of money hiring these specialists with their

unreliable and extremely slow weapons on the continent.

Initially both parties had little reason to recruit from abroad because England was full

of unemployed former soldiers. Only when it came to the relatively new firearms had England

considerable unfulfilled demand. Artillery had already proven its importance in the final

phase of the Hundred Years' War, especially during sieges, but also increasingly in battle.

Though there were gun founders and gunners in England, they were nowhere near the quality of

the those of the French and Burgundians. The first "handgonners" equipped with portable

firearms seemed to have been exclusively foreigners. Despite the fact that there were thousands

of experienced archers available, many commanders - all seasoned veterans who knew what they

were doing - spent increasingly large amounts of money hiring these specialists with their

unreliable and extremely slow weapons on the continent.

That these firearms had their own problems became evident in 1461 in the Second Battle of St. Albans. Edward's ally the Duke of Warwick had some Burgundian gunners and handgonners among his troops, but as a result of sleet their powder got wet so that many of them were massacred before they could fire their guns.

But these few specialists marked only the beginning. After the first phase of the Wars of the Roses the leaders of the defeated party normally fled into exile on the continent and returned later with recruited mercenaries. The first had been Queen Margaret, the driving force of the Lancaster resistance, who went to her cousin King Louis XI of France and asked for help. He supplied her with one of his most seasoned captains, Pierre de Breze, along with several hundred soldiers. With this force she sailed to Scotland with French money to recruit more troops. Later she waged war in the north for some time quite successfully, until the Lancaster forces were defeated decisively at Hexham in 1464.

Edward IV reigned relatively undisturbed from this point, until he fell out with the powerful Duke of Warwick. At first Warwick was victorious but finally he too was defeated and had to flee to France in 1470. There Margaret was still at work gathering English emigrants and asking for money from King Louis, who already had enough trouble on his hands and therefore no interest at all in a new war with England. But Edward had formed an alliance with the rebellious Duke of Brittany and married his sister to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Furthermore he had provided both dukes with larger contingents of the still very popular English archers. Confronted with a rematch of the old alliances from the Hundred Years' War, Louis finally gave his support to the newly formed alliance between the former arch-enemies Warwick and Margaret, and endowed it generously with money and ships.

This alliance proved too strong for Edward; abandoned by most of his allies, he was forced to flee without a fight. He went to Holland to the court of the Duke of Burgundy. At first Charles the Bold didn't show much interest in his poor exiled brother-in-law, but when relations with France deteriorated again he provided Edward with 1,500 German and Burgundian mercenaries, including 300 Flemish handgonners, and had the necessary ships built. With this force Edward landed in England in 1471, where he was joined by many noblemen who had become dissatisfied with Warwick's regime.

Shortly thereafter, Edward crushed his opponents one after the other at Barnet and then at

Tewkesbury, where the artillery played a crucial role. Warwick and the Lancaster heir to the

throne had both fallen, Margaret was imprisoned for years until she was ransomed by Louis XI,

while poor Henry VI was probably murdered in prison shortly after. Lancaster was decisively

defeated and the Wars of the Roses seemed concluded. Nevertheless, the old conflict with

France was still smouldering. Encouraged by Charles the Bold, Edward landed in 1475 in Calais

with a large army to march on Paris once again, together with Burgundy. But Charles the Bold

wanted to leave the dirty work to the English and held his own troops back. As a result, Edward

finally accepted a generous tribute from Louis XI and went back home.

Shortly thereafter, Edward crushed his opponents one after the other at Barnet and then at

Tewkesbury, where the artillery played a crucial role. Warwick and the Lancaster heir to the

throne had both fallen, Margaret was imprisoned for years until she was ransomed by Louis XI,

while poor Henry VI was probably murdered in prison shortly after. Lancaster was decisively

defeated and the Wars of the Roses seemed concluded. Nevertheless, the old conflict with

France was still smouldering. Encouraged by Charles the Bold, Edward landed in 1475 in Calais

with a large army to march on Paris once again, together with Burgundy. But Charles the Bold

wanted to leave the dirty work to the English and held his own troops back. As a result, Edward

finally accepted a generous tribute from Louis XI and went back home.

Edward enjoyed a peaceful life until his death in 1483, while Louis XI took care of Burgundy. He secretly roused the Swiss to war against Charles the Bold, who came to a miserable end in the battle at Nancy (1477). But the crafty Louis reaped only a small part of the rewards, because the Habsburgs took the lion's share of the Burgundian inheritance. And while it seems that these events happened far away on the continent, they without doubt caused repercussions for the Wars of the Roses, which would have been over after the battle of Towton in 1461 were it not for the support of France or Burgundy. Events on the continent dictated where the defeated could find help in the form of primarily money and mercenaries.

As long as Edward governed he stayed away from the conflict between France and Habsburg. But when, after his death, his brother Richard Duke of Gloucester took the throne for himself and had some disaffected nobles executed, a new surge of emigrants fled to the continent. Most gathered around Henry Tudor, a Welsh nobleman who had always been a loyal partisan of the Lancaster and had moved to Brittany.

The situation worsened when Louis XI died in the summer of 1483, and his sister Anne de Beaujeu exercised the regency for his eleven year old son. Some of the senior nobles tried to engineer this situation to their benefit. The Duke of Orleans hoped to become king and allied himself with the Duke of Brittany and Maximilian of Habsburg. Richard III was willing to join the coalition and send his archers to Brittany, but first he demanded the extradition of Henry Tudor and the other exiles. These fled to France and asked for support there.

They were forced to wait for some time. However, when in March 1485 the poorly planned revolt of the Duke of Orleans failed, Anne de Beaujeu was ready to see about the English problem. After the revolt had been quickly brought under control, she was left with many troops who it would have been best to deport overseas, before they caused trouble at home. She gave Henry Tudor a loan of 40,000 livres to start recruiting. The biggest contingent was comprised of 1,000 Scots who had been brought to France to fight the Duke of Orleans, and who now showed little inclination to return home so rapidly. The number of French - discharged mercenaries, Bretons, gunners and adventurers - is estimated at perhaps 1,800. These numbers were finally augmented with a few hundred English exiles.

With this relatively small army Henry Tudor landed in Wales in August, where he recruited

more men from among his followers there. Since it is assumed, however, that in the

ensuing battle of Bosworth he had only about 5,000 men at his disposal, foreign mercenaries

must have made up over half of his army. On the side of Richard III a Spanish captain Juan

Salaçar (also Salazar) is mentioned, who was normally in the service of Maximilian

of Habsburg; it is possible that he served with some Burgundian heavy cavalry in the Yorkist

army. The battle was finally decided by Lord Stanley who commanded Richard's strongest

contingent and changed sides during the battle.

With this relatively small army Henry Tudor landed in Wales in August, where he recruited

more men from among his followers there. Since it is assumed, however, that in the

ensuing battle of Bosworth he had only about 5,000 men at his disposal, foreign mercenaries

must have made up over half of his army. On the side of Richard III a Spanish captain Juan

Salaçar (also Salazar) is mentioned, who was normally in the service of Maximilian

of Habsburg; it is possible that he served with some Burgundian heavy cavalry in the Yorkist

army. The battle was finally decided by Lord Stanley who commanded Richard's strongest

contingent and changed sides during the battle.

The victory of Bosworth initiated the reign of the Tudors and officially ended the Wars of the Roses. But there were still some members of the Yorks who now fled to Burgundy, where the sister of Richard III and widow of Charles the Bold was an influential person at court. She mediated the services of the German mercenary captain Martin Schwarz (in English often Swartz), one of the early military contractors, who provided the new infantry pikemen, the Landsknechts. A former shoemaker from Augsburg, Schwartz came from a humble background but had quickly made a name for himself. Already by 1475 he had distinguished himself at the siege of Neuss, and was then knighted by Maximilian himself in the war for the Netherlands. Under his command many Swiss served who at that time were still important for giving the Landsknechts the necessary self-confidence.

Together with John de la Pole, a nephew of Richard III, Schwartz led 2,000 German, Swiss and Flemish mercenaries to Ireland, where they crowned a certain Lambert Simnel as Edward VI. Then they recruited about 5,000 Irishmen, mostly light-armed Kern with short swords and spears and no body armour. In addition, there were several English nobles with their retainers. Altogether there were between 7,000 and 8,000 men who landed in England in 1487.

There, in June, near Nottingham, the battle of Stoke was fought. The royal army was at least twice as strong and opened the fight with a devastating salvo from their archers. The victims were mainly the unarmoured Irishmen who were "full of arrows like hedgehogs", as some sources reported. Although among the Landsknechts and Swiss only the first files normally wore armour, they seem to have survived the hail of arrows pretty well. They attacked the English centre in their usual pike square formation and were only stopped after the English had suffered severe losses.

Attacked from both sides by knights and archers, they made a desperate last stand. It seems

that they refused to let their lives go for nothing, as 3,000 Tudor casualties almost certainly

fell to their pikes. Of the mercenaries themselves only about 200 survived the battle and, in

contrast to the captured English and Irishmen, were pardoned and allowed to return home.

Attacked from both sides by knights and archers, they made a desperate last stand. It seems

that they refused to let their lives go for nothing, as 3,000 Tudor casualties almost certainly

fell to their pikes. Of the mercenaries themselves only about 200 survived the battle and, in

contrast to the captured English and Irishmen, were pardoned and allowed to return home.

Incidentally, it is one of the strange twists in history that Richard de la Pole, the younger brother of the fallen John, later led German mercenaries in French pay. The alliance between England and France had soon given way to realpolitik. And so the Tudor kings also renewed the old alliance with Habsburg/Burgundy against France. The last York, which meant by then de la Pole, looked for help in France as had the Tudor exiles before him. Richard de la Pole, the last York candidate for the English crown, fell as commander of the famous "Black Band" at the battle of Pavia in 1525.