Fighting the Maroons of Suriname

Slaves for fourpence a day

In the 18th Century, the sugar plantations in the Caribbean were a source of almost untold riches. Although some dissenting voices in Europe were critical of the brutal methods used to exploit black slaves, the triangular trade that developed around them proved astoundingly profitable. Cheap European manufactured goods were first exchanged for slaves in West Africa, who were then traded for sugar or rum in the West Indies, which could be subsequently sold in Europe for a fortune. With these enormous profits the sugar barons were not only able to increase their own wealth, but were also able to influence policy in their favor. The only flaw in this almost perfect business was that the slaves had a tendency to escape from their bonds any chance they could, and since the number of the slaves far surpassed that of their white captors there was always the simmering threat of a bloody rebellion. A very special source of annoyance for plantation owners were the so-called

"Maroons," runaway slaves who had managed to escape into the jungle or the

mountains, where they formed mini communities. These small bands of Africans living in

freedom threatened the security and stable existence of the planters, who, while

contending with repeated raids by the Maroons on isolated plantations, also feared that

the Maroons would set an example for the other slaves. Although they didn't want open war

with the powerful whites, the Maroons needed weapons, tools, food and especially women,

to survive in the jungle; all of these things could only be obtained from the plantations.

A very special source of annoyance for plantation owners were the so-called

"Maroons," runaway slaves who had managed to escape into the jungle or the

mountains, where they formed mini communities. These small bands of Africans living in

freedom threatened the security and stable existence of the planters, who, while

contending with repeated raids by the Maroons on isolated plantations, also feared that

the Maroons would set an example for the other slaves. Although they didn't want open war

with the powerful whites, the Maroons needed weapons, tools, food and especially women,

to survive in the jungle; all of these things could only be obtained from the plantations.

Although these skirmishes against runaway slaves were a more or less permanent fixture of all planter colonies, they nonetheless failed to bring about a decisive victory against the Maroons. Usually only minor interventions by the police were called for, but now and then major rebellions flared up, as in 1761 in Berbice, which struck the whole colony and could only be suppressed by a large number of troops brought over from Europe. The situation was particularly dangerous in the Dutch colony of Suriname, where there were 25 slaves for every white man. In the plantation districts this number climbed up to 65, compared with the average ratio on the West Indian islands, which was 10:1. The planters called in the military at every opportunity, but doing so was expensive, and the Government sent fresh troops only if the number of runaway slaves or the severity of the raids exceeded a certain limit, at which point they destroyed a few villages and fields in the jungle and with luck even killed some Maroons.

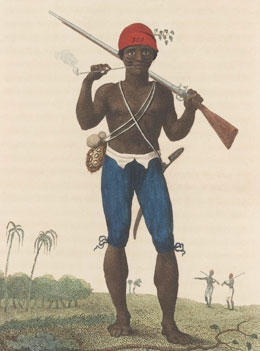

In order to have his own police force under his command, the governor finally ordered the formation of the "Neeger Vrijcorps" which originally consisted of 116 slaves, who had been bought especially for that purpose and had been promised their freedom. These "Rangers" were paid relatively well and proved themselves to be brave and reliable in the fight against the Maroons. To further stimulate their motivation they received additional bounties, such as 25 guilders for every hand of a rebel.

The hunt for runaway slaves and the suppression of smaller revolts make for trivial and sordid stories. Great armies were not moved for such inconsequentialities and these events are normally relegated to footnotes by miltary historians. Nevertheless, these fights settled the fate of many mercenaries. In the most remote corners of the world, on the widely scattered Indonesian islands, in the tiny forts on the African Slave Coast, in the Indian jungles or in the mangrove swamps of Guiana, small groups of soldiers struggled in the wilderness and perished there anonymously. Usually warfare in the 18th Century is associated with glorious battles like Malplaquet, Fontenoy and Rossbach; however, the Dutch sent 655,200 men to Asia in that century alone, of which only 252,500 returned. The rest had been consumed in good part by small wars and illnesses.

Conditions in the Suriname colony deteriorated further. Many planters had moved to Holland with their millions and left their plantations in the care of overseers, whose activity was linked inextricably with profit rate. In many areas monocultures had exhausted the soil, while at the same time the price of sugar dropped. All this led to even more brutal exploitation of the slaves, and in turn provoked new waves of runaways and a reinforcement of the Maroons. Under their charismatic leaders Baron and Boni the Maroons made increasingly bold raids to provide themselves with the necessary goods and women. When the colonists became fearful of yet another new massacre and pled with increasing urgency for help, the Dutch West India Company sent 800 soldiers from Holland under the command of the Swiss colonel Louis Henry Fourgeoud, who had already distinguished himself during the revolt in Berbice. These mercenaries were mostly German, Swiss, English and Scots, and their story was related by the Scottish officer Captain John Gabriel Stedman (Narrative of a five years' expedition against the revolted negroes of Surinam).

Soon after their arrival in early 1773 the soldiers set off in small groups into the

jungle. Numerous rivers, mangrove swamps and flood plains impeded their progress. They

fought their way through the undergrowth, waded through swamps and swam across rivers.

Torrential downpours alternated with unrelenting rain. When it was not raining, the hot

jungle steamed moisture. Everything was wet, food and leather gear moldered. Feet became

swollen and inflamed in wet boots; small scratches turned into festering wounds. Dirty

water and rotten food led to dysentery and typhus, which were soon boosted by tropical

diseases like malaria and yellow fever. After just a few months, the corps had dwindled

to three quarters of its original strength. The surviving mercenaries had yet to confront

any of the Maroons; instead ring-worms, leeches, mosquitoes, sand fleas, lice and vermin

of all kinds had to be contended with first, as well as crocodiles, pumas, vampire bats,

anacondas, scorpions and poisonous spiders. Only a group of 30 men under a lieutenant

Lepper encountered Maroons. Crossing a swamp they fell into an ambush; with their powder

wet and up to their shoulders in water, most were shot down in the swamp and the rest

killed on the shore.

Soon after their arrival in early 1773 the soldiers set off in small groups into the

jungle. Numerous rivers, mangrove swamps and flood plains impeded their progress. They

fought their way through the undergrowth, waded through swamps and swam across rivers.

Torrential downpours alternated with unrelenting rain. When it was not raining, the hot

jungle steamed moisture. Everything was wet, food and leather gear moldered. Feet became

swollen and inflamed in wet boots; small scratches turned into festering wounds. Dirty

water and rotten food led to dysentery and typhus, which were soon boosted by tropical

diseases like malaria and yellow fever. After just a few months, the corps had dwindled

to three quarters of its original strength. The surviving mercenaries had yet to confront

any of the Maroons; instead ring-worms, leeches, mosquitoes, sand fleas, lice and vermin

of all kinds had to be contended with first, as well as crocodiles, pumas, vampire bats,

anacondas, scorpions and poisonous spiders. Only a group of 30 men under a lieutenant

Lepper encountered Maroons. Crossing a swamp they fell into an ambush; with their powder

wet and up to their shoulders in water, most were shot down in the swamp and the rest

killed on the shore.

After this experience they tried ships. Stedman set off in July in two armed barges with 65 men including some of the Rangers. In a settlement with the homely name of "Devil's Harwar" they met a survivor of Lepper's troop, whom the Maroons had left behind for dead, and who now detailed the fate of his comrades. With Devil's Harwar as a base they rowed on through endless mangrove swamps and incessant rain. Often they had to sleep in the overcrowded barges because there was no dry place to be found. On the small mud islands the sleeping men were easy pickings for crocodiles. All went hungry, were covered in insect bites, and were more or less seriously ill. When the expedition was cancelled after two months without any enemy contact at all, Stedman had a total of 20 men left. But even these were in a deplorable state, exhausted, demoralized, their uniforms in rags. Stedman noted, "A band of such scarecrows as could have disgraced the garden or fields of any farmer in England. Among them was a Society captain named Larcher, who declared to me he never combed, washed, shaved, or shifted, or even took off his boots, till all was rotted from his body."

Fourgeoud allowed his exhausted troops to rest in Paramaribo, then drove them back into

the jungle. This time they discovered several abandoned villages and rice fields and

burned them down. They also found the remains of Lieutenant Lepper and his men: seven

skulls on poles. Far off from any supply routes, food became scarce. The officers clamped

down on the men with extreme brutality to maintain order. During a riot they beat up a

mercenary with such savagery that he died shortly afterwards from his injuries. Some

couldn't bear the exertion, for them fever was a relief, and without inner resistance

they laid down and died. Others hanged themselves in despair.

Fourgeoud allowed his exhausted troops to rest in Paramaribo, then drove them back into

the jungle. This time they discovered several abandoned villages and rice fields and

burned them down. They also found the remains of Lieutenant Lepper and his men: seven

skulls on poles. Far off from any supply routes, food became scarce. The officers clamped

down on the men with extreme brutality to maintain order. During a riot they beat up a

mercenary with such savagery that he died shortly afterwards from his injuries. Some

couldn't bear the exertion, for them fever was a relief, and without inner resistance

they laid down and died. Others hanged themselves in despair.

This pattern was repeated over the years. If the hospitals in Paramaribo and Fort Amsterdam declared that enough soldiers were fit for duty new expeditions were sent into the jungle, from where, mere months later, only miserable parts returned. If they were lucky they destroyed a few villages and their crops, but real fighting virtually never happened. One group under a captain Meyland was ambushed in a swamp and nearly annihilated. At the beginning of 1775, 400 fresh mercenaries arrived from Holland as reinforcements and Fourgeoud dismissed some of the most invalid. But despite the replacements he had only 180 operational men under his command when he departed in July on a new expedition. Reinforced by 100 Rangers they succeeded in capturing Boni's main base Gado Saby, the only presentable success of the entire war. On the way to Gado Saby they had to cross yet again countless rivers and marshes. On one shore they came upon the rotting remains of Meyland and his men.

At Gado Saby they ran into a fierce firefight with the Maroons, but losses were quite low as the Maroons, lacking lead, shot with pebbles and buttons, which caused only minor flesh wounds. Finally, the Maroons withdrew into the surrounding jungle. At night they fired on the intruders and shouted insults at them. It's interesting how they commented on the situation of the European mercenaries. "They told us that we were to be pitied more than they; that we were white slaves, hired to be shot and starved for fourpence a day; that they scorned to waste much more of their powder upon such scarecrows." While the Maroons demonstrated some pity for the mercenaries, they promised unambiguously to exterminate the planters and Rangers. Maroons and Rangers called each other traitors and persecuted each other with implacable hatred. To demonstrate their contempt, the Rangers played "bowls with those very heads they had just chopped off from their enemies", or smoked the noses and ears of dead Maroons to use them as trophies.

After the fall of Gado Saby the Maroons disappeared without trace in the jungle. The

soldiers searched through mud and marshes without firing a shot. Sometimes they had to

wade for hours through deep water, where some were even caught by crocodiles. If they

couldn't find a muddy hill to spend the night, they had to hang their hammocks in the

trees. Without fire, the mosquitoes were an even more intolerable plague than the vampire

bats. Food and supply were constantly scarce, and in the rare trading posts the

mercenaries were forced to spend the last of their money buying food at exorbitant

prices. When somebody died of exhaustion and fever the others felt neither pity nor

sorrow, but only asked: "Has he left any brandy, rum or tobacco?" Nevertheless

the Maroons were hit hard by the destruction of their villages and fields. They suffered

severely from lack of food and had to retreat further and further inland. But for every

scorched field some mercenaries had to pay with their lives, until finally only a

tattered band of fever-ridden, miserable wretches returned to Fort Amsterdam.

After the fall of Gado Saby the Maroons disappeared without trace in the jungle. The

soldiers searched through mud and marshes without firing a shot. Sometimes they had to

wade for hours through deep water, where some were even caught by crocodiles. If they

couldn't find a muddy hill to spend the night, they had to hang their hammocks in the

trees. Without fire, the mosquitoes were an even more intolerable plague than the vampire

bats. Food and supply were constantly scarce, and in the rare trading posts the

mercenaries were forced to spend the last of their money buying food at exorbitant

prices. When somebody died of exhaustion and fever the others felt neither pity nor

sorrow, but only asked: "Has he left any brandy, rum or tobacco?" Nevertheless

the Maroons were hit hard by the destruction of their villages and fields. They suffered

severely from lack of food and had to retreat further and further inland. But for every

scorched field some mercenaries had to pay with their lives, until finally only a

tattered band of fever-ridden, miserable wretches returned to Fort Amsterdam.

During recovery periods in the garrisons almost all soldiers lived with slave women, indeed Stedman and some officers even married slaves. Many had far more sympathy for slaves than for the arrogant Dutch planters. In the cities they bore constant witness to the brutal penalties which were often imposed for minor trespasses. Even though they were white themselves, in the eyes of the planters they rated only a little above the slaves. During their expeditions in the jungle they had learned to appreciate the loyalty and bravery of their black brothers in arms, without whom no one would have returned alive. Stedman's book is full of compassion for the cruelly exploited and oppressed slaves. However they were not revolutionaries but mercenaries, and they took their pay from the Dutch and hoped to somehow survive their period of service. Moreover, the rank and file were far too busy with their own miserable conditions. They hated their officers and the planters, who forced them into the jungle over and over again.

In the summer of 1776 the end of their misery seemed to be within sight. It was said that the Maroons were practically starving and were on the verge of capitulation. New Ranger companies were formed, and the mercenaries were looking forward to going back home. At one point, transport ships even harboured in Paramaribo and the troops boarded. Everyone was glad to have escaped that hell alive. But then the order came to go back once again into the jungle. The news caused turmoil among the soldiers and had they had a determined leader they probably would have attacked their officers and mutinied. But the officers brought the dangerous situation quickly under control. A triple cheer on the King of Holland was ordered, and when the soldiers stayed silent the officers pounced on them, beating them with swords and pistols. Finally, after several gallons of gin had been promised, some soldiers joined the cheers of the officers. When order seemed to be restored the troops disembarked. In the end, some 160 seriously ill were transported back to Holland, while the rest marched dejectedly back into the jungle. There they no longer undertook raids, but listlessly dragged themselves from one camp to another. Even the officers were too exhausted to push the men any harder. When at last news came that the Maroons had fled to French Guyana the war was regarded as over.

Fourgeoud's campaign was celebrated as a major victory with 21 villages and more than 200

fields destroyed. But the price was immense. When the troops were finally embarked in

April 1777, only about 100 of the 1,200 men who had been sent to Suriname over the course

of those four years remained. Of these 100, however, there were only 20 who could have

been considered more or less healthy. Stedman was the only officer who had arrived from

Europe with the first division, and the old warhorse Fourgeoud died exhausted and burned

out shortly after his arrival in Holland. As a replacement 350 new soldiers arrived from

Holland, many of whom were already suffering from scurvy and other diseases.

Fourgeoud's campaign was celebrated as a major victory with 21 villages and more than 200

fields destroyed. But the price was immense. When the troops were finally embarked in

April 1777, only about 100 of the 1,200 men who had been sent to Suriname over the course

of those four years remained. Of these 100, however, there were only 20 who could have

been considered more or less healthy. Stedman was the only officer who had arrived from

Europe with the first division, and the old warhorse Fourgeoud died exhausted and burned

out shortly after his arrival in Holland. As a replacement 350 new soldiers arrived from

Holland, many of whom were already suffering from scurvy and other diseases.

Stedman's report leaves no doubt that the black Rangers were far superior to the European mercenaries, not only as combatants but also in terms of their motivation and reliability. This raises the question of why these inefficient Europeans were transported with great difficulty to South America. The answer is as banal as it is cruel: "Free" Europeans were by far much cheaper than black slaves. A healthy slave in Suriname cost at least 500 - 1,000 Fl, while a mercenary could be had for a mere 10 - 30 Fl. This unsentimental conclusion furthermore explains why sailors on the infamous slave ships were often treated worse than the precious "human merchandise". Studies estimate a death rate of 17.9% among the crew versus 12.3% among the slaves.