War for Diamonds

Executive Outcomes in Sierra Leone.

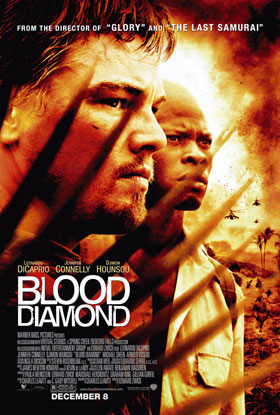

Many people who saw the movie "Blood Diamond" learned for the first time something about the

terrible war in Sierra Leone and the trade in blood diamonds, but they were also confronted

with a completely new type of mercenary. Suddenly we were dealing with the 32nd "Buffalo"

Battalion, whereas before in the films of Van Damme, Stallone & Co there was only talk of the

Foreign Legion or the Vietnam War. Rather than exposing a half-naked, ripped body wearing the

- since Rambo - almost obligatory headband, protagonist Danny Archer (Leonardo DiCaprio)

instead displays a powerful knowledge of diamonds and the international financial community;

instead of toting heavy machine guns or rocket launchers, his weapon of choice is his cell

phone. His fellow mercenaries act with the same professionalism: they establish training camps,

impressive depots with Russian transport planes lurking in the background, and communications

systems.

Many people who saw the movie "Blood Diamond" learned for the first time something about the

terrible war in Sierra Leone and the trade in blood diamonds, but they were also confronted

with a completely new type of mercenary. Suddenly we were dealing with the 32nd "Buffalo"

Battalion, whereas before in the films of Van Damme, Stallone & Co there was only talk of the

Foreign Legion or the Vietnam War. Rather than exposing a half-naked, ripped body wearing the

- since Rambo - almost obligatory headband, protagonist Danny Archer (Leonardo DiCaprio)

instead displays a powerful knowledge of diamonds and the international financial community;

instead of toting heavy machine guns or rocket launchers, his weapon of choice is his cell

phone. His fellow mercenaries act with the same professionalism: they establish training camps,

impressive depots with Russian transport planes lurking in the background, and communications

systems.

The film presented a new kind of mercenary, represented by a group which if you hadn't already heard of them, you would soon be reading about in the reviews: Executive Outcomes. Still, behind this well-made but superficial decoration, the film rapidly fell back on the old clichés about mercenaries. While Danny Archer ultimately discovers he has a good heart, his comrades are irredeemably bad. The differences between them and the butchers of the RUF boil down to the fact that they look cooler and carry more technology while plying their trade - they are, in short, more professional. Beyond this they are possessed by the same greed for diamonds, are totally unscrupulous, and display a willingness to go for each other like wild animals at the slightest provocation.

Ultimately, every modern war is about money, power or raw materials. In Sierra Leone many people were trying to make some money from diamonds, not least some senior officers of UN contingents. But the story became much more interesting when international companies like De Beers began secretly pulling strings and sinister mercenaries started taking care of their dirty work. Although this is the stuff from which legends - or, indeed, thrilling Hollywood screenplays - are forged, it is worth a little effort all the same to examine more closely what Executive Outcomes actually did in Sierra Leone.

The civil war in Sierra Leone started in 1990 with an offensive by the RUF (Revolutionary

United Front) out of Liberia. Its leader, Foday Sankoh, a former colonial soldier and

professional revolutionary, had met during his exile in Libya Charles Taylor who later came

to power in Liberia. Taylor supported the RUF because he wanted access to the diamonds of

Sierra Leone to fund his own war. The rank and file of the RUF was mainly recruited from

hapless youth who were full of hatred for anyone with a little more than themselves. Soon,

however, more and more child soldiers were abducted by the RUF on their raids. To increase

their fighting morale they were plied with huge quantities of alcohol and drugs, and unspeakably

cruel warfare was waged against the civilian population. Among countless atrocities and

massacres, the RUF became notorious for chopping off limbs, something that eventually became

a kind of trademark.

The civil war in Sierra Leone started in 1990 with an offensive by the RUF (Revolutionary

United Front) out of Liberia. Its leader, Foday Sankoh, a former colonial soldier and

professional revolutionary, had met during his exile in Libya Charles Taylor who later came

to power in Liberia. Taylor supported the RUF because he wanted access to the diamonds of

Sierra Leone to fund his own war. The rank and file of the RUF was mainly recruited from

hapless youth who were full of hatred for anyone with a little more than themselves. Soon,

however, more and more child soldiers were abducted by the RUF on their raids. To increase

their fighting morale they were plied with huge quantities of alcohol and drugs, and unspeakably

cruel warfare was waged against the civilian population. Among countless atrocities and

massacres, the RUF became notorious for chopping off limbs, something that eventually became

a kind of trademark.

The army of Sierra Leone, the RSLMF (Republic of Sierra Leone Military Forces), was no real match for the RUF. Many of its soldiers had been forcibly recruited, had received no training whatsoever, and only in exceptional cases received any kind of pay. They too were awash with drugs and alcohol, and subsisted on plunder. When they clashed with the enemy, they typically retreated after only a brief exchange of fire, if they obeyed orders to engage at all. Under these circumstances the RUF, well supported by Libya and Charles Taylor, rapidly gained ground in the Southeast. Before long they controlled the first diamond mines and were able to purchase weapons on the free market through the sale of blood diamonds.

While the RUF victoriously pushed forward, hacking off hands and feet by the thousands and putting to flight hundreds of thousands more, some low-paid officers overthrew the government in Freetown and put Captain Valentine Strasser into power. This had very little influence on the effectiveness of the armed forces however. Strasser managed to convince a few West African countries - Nigeria, Ghana and Guinea, the so called ECOMOG - to intervene. Although each country sent a reinforced battalion, even these troops were unable to halt the RUF's progress or drive them back to Liberia. Meanwhile, the RUF had occupied a good part of the mining area and impeded with their presence the exploitation of the other mines. Desperate, Strasser contracted the British security firm GSG (Gurkha Security Guards) at the beginning of 1995 to protect the mining area. With a force of only 60 men, GSG weren't up to the task; after their commander, the American Bob MacKenzie, and some Gurkhas had been killed in a skirmish with the RUF, GSG were eventually forced to withdraw.

From this point the situation deteriorated almost in free fall. The unpaid government troops pillaged the country nearly as thoroughly as the RUF, and the ECOMOG soldiers who were dug in with their heavy equipment at the airport were left frantically trying to protect themselves. Freetown was flooded with refugees waiting like lambs for the arrival of the butchers of the RUF. The situation was so desperate that speculation was rife the government would only last for a matter of months, if even weeks. It was at this point that the cavalry arrived, and Executive Outcomes entered the stage.

Strasser later claimed that he became aware of the company from an article in Newsweek. While this may be true, it's likely that the article was laid in his hands with a few warm words of suggestion. To his great luck the triumph of the RUF turned out to be a major problem for some other people. In Sierra Leone the big mining companies had profitably mined not only diamonds but also bauxite and rutile. That they had bribed corrupt politicians, exploited their laborers and paid as little tax as possible goes without saying, but they had no interest in a civil war that brought their good business to a halt. Despite protecting their mines with private security personnel, for some it still wasn't possible to operate effectively, and many wrote off their investments and brought their employees to safety. There were also others who were ready to seize the opportunity and invest new venture capital - given the situation, prices had plummeted and the desperate government was willing to sign almost any kind of contract.

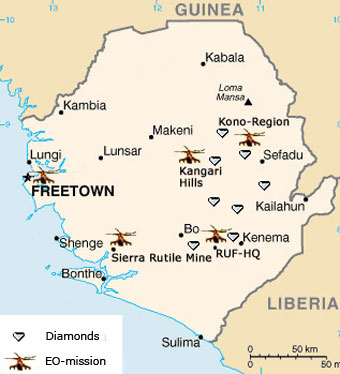

The British company Branch Energy played a decisive role here, and had as a major shareholder Tony Buckingham, one of the founders of Executive Outcomes. In short, Branch Energy and Executive Outcomes were after a fashion sister companies, largely owned by the same people, albeit officially independent. Branch Energy was relatively new in Sierra Leone and, unlike many competitors, keen to expand its presence. Therefore at the height of the crisis it founded a joint venture with Strasser for diamond mining and received large mining concessions in the Kono region (near Koidu). It is probable that on this occasion Buckingham and his accountant Michael Grunberg called Strasser's attention to the services of Executive Outcomes and offered the initial funding. Additional financing was probably provided by the Australian-American company Sierra Rutile, whose most profitable rutile mine was occupied by the RUF.

The truth about the many secret agreements and transactions involved at this time will almost certainly never be completely known, but the wider context is evident. Branch Energy was promised new diamond mines, Sierra Rutile was to re-open their operation, while Strasser's government closed a deal with Executive Outcomes for 200 mercenaries to train the RSLMF and provide logistical assistance as well as combat support, all for a monthly payment of $1.8 million.

In May 1995 the first 50 mercenaries arrived in Freetown (followed six months later by another

130) and began forming the first units. They were under intense time pressure, as the RUF

had already brought the fighting as close as the suburbs. Shortly after when the battle for

Freetown flared up, the mercenaries proved to be a critical part of the action, bringing two

BMP-2 infantry fighting vehicles and an Mi-24 (Hind) helicopter gunship along with the

hastily trained troops. The RUF suffered its first major defeat; about 200 of its fighters

were killed and about 1,000 of them deserted.

In May 1995 the first 50 mercenaries arrived in Freetown (followed six months later by another

130) and began forming the first units. They were under intense time pressure, as the RUF

had already brought the fighting as close as the suburbs. Shortly after when the battle for

Freetown flared up, the mercenaries proved to be a critical part of the action, bringing two

BMP-2 infantry fighting vehicles and an Mi-24 (Hind) helicopter gunship along with the

hastily trained troops. The RUF suffered its first major defeat; about 200 of its fighters

were killed and about 1,000 of them deserted.

Executive Outcomes used this much-needed respite for the formation of new fighting units. Instead of using unreliable government troops, they enlisted the so-called Kamajors, local hunters mostly from the Mende people. Excellent trackers, they had already formed self-defense militias against the attacks of the RUF in some parts of the country. Now they were supplied with modern weapons and trained for guerrilla warfare in collaboration with other units. The Kamajors became the eyes and ears of Executive Outcomes, while also making up a large part of the combat troops used in the following phase.

In guerrilla warfare in the African bush, where there is a lack of solid front lines, reconnaissance, concentration of firepower, speed and ambushes all play crucial roles. As former members of South African elite units during the war in Angola, most of the mercenaries had plenty of experience with these tactics. Reconnaissance was mainly carried out by the Kamajors and a special airplane, ambushes were avoided by transporting troops with helicopters, and firepower was provided by the dreaded Mi-24 gunships, along with two Alpha Jets dispatched by the Nigerian Air Force for support.

The first operations were directed against the RUF bases in the vicinity of Freetown. Within a few days the RUF had been completely expelled from the mining area of Kono. The only losses for Executive Outcomes were two dead Kamajors and five wounded, with a further two mercenaries wounded. The RUF, in contrast, suffered hundreds of dead and many more deserters. Most importantly, however, was that in losing the mines the rebels lost their main source of income. Subsequent missions followed a similar pattern. First, the enemy positions were precisely reconnoitred, followed by intense bombardment by the Nigerian Alpha Jets. The already demoralised enemy was then attacked by small mobile combat groups supported by mortar fire, armoured vehicles, land rovers with heavy machine guns and the helicopter gunships. Driven from their positions, the rebels usually fled directly into ambushes of Kamajor groups previously flown in by helicopters.

At the end of 1995 the Sierra Rutile mine was recaptured. Executive Outcomes next prepared

a decisive blow against an RUF camp in the Kangari hills. For this operation 200 additional

mercenaries were flown in from South Africa. Again, they worked swiftly, precisely and with

minimal losses. The RUF, however, not only lost many of their fighters but also some important

officers from their senior cadres. Constantly harassed by helicopter gunships and pursued by

mobile Kamajor units, the RUF finally indicated its willingness to initiate peace talks and

demanded a cease-fire.

At the end of 1995 the Sierra Rutile mine was recaptured. Executive Outcomes next prepared

a decisive blow against an RUF camp in the Kangari hills. For this operation 200 additional

mercenaries were flown in from South Africa. Again, they worked swiftly, precisely and with

minimal losses. The RUF, however, not only lost many of their fighters but also some important

officers from their senior cadres. Constantly harassed by helicopter gunships and pursued by

mobile Kamajor units, the RUF finally indicated its willingness to initiate peace talks and

demanded a cease-fire.

In the meantime the first free elections in Sierra Leone had taken place, with Ahmad Tejan Kabbah elected as president. He was determined to end the civil war. To reorganise the devastated country he needed financial assistance from the World Bank and the IMF, but these forcefully demanded a reduction in the huge budget deficit. Most of the country's money was being spent on food subsidies for its ineffective army, which was necessary to prevent more hungry and unemployed youths enlisting with the rebels, and as a result these funds were off limits for the government, which left only the money used for paying Executive Outcomes. Kabbah negotiated with the company and achieved a reduction in the monthly payments and agreed to finish the contract at the end of the year.

The guerrilla war in the bush continued, even though there hadn't been any major fighting since the armistice. The RUF had used the time to regroup their forces and bring in new equipment from Liberia. It planned a new offensive against Freetown. Due to its excellent reconnaissance - supplied by Kamajors, radio monitoring and aerial photographs - Executive Outcomes already knew about these preparations. After President Kabbah had been informed he gave permission to strike. In September 1996, with the usual cooperation of mercenaries, Kamajor battle groups and Nigerian air support, a large rebel camp in the southeast was completely destroyed. The RUF suffered such heavy losses that it consented to serious negotiations and in November the Abidjan Peace Accord was signed.

Of course no one was naive enough to think that the war was now over, but many probably hoped that at least the worst was behind them. The IMF and, as a result, President Kabbah increasingly urged that the expensive mercenary contract had to come to an end, and finally in January 1997 Executive Outcomes left the country. Overall for them it hadn't been a particularly profitable engagement. Of the contracted $35.3 million, only $15.7 million had been paid, and the company probably evaded bankruptcy only because of its reserves accumulated in Angola. However, it can be assumed that in the end the real owners of Executive Outcomes were amply rewarded with their shares in Branch Energy.

Shortly before their departure some officers warned President Kabbah of a military coup - the RSLMF felt their privileges were being threatened by the increased importance of the Kamajors. As a replacement for the mercenaries, 900 Nigerian soldiers arrived in Freetown to protect the president. The security of Diamond Works' diamond mines was taken over by Life Guard, a kind of subsidiary of Executive Outcomes. But even this didn't help much: after a military coup in May, Kabbah was forced to flee into exile. The officers leading the revolt allied themselves with the RUF in the fight against the West African contingent (now ECOWAS) defending the airport and the Kamajor militias. Freetown succumbed to a days-long orgy of blood and violence which saw the ECOWAS troops engage only to fire their heavy artillery from the airport, causing thousands of deaths, among whom were certainly some rebels.

The bloody civil war then dragged on for several more years as tens of thousands were slaughtered and mutilated. The low-paid or completely unpaid UN troops mostly protected themselves, while some even became involved in the lucrative trade in blood diamonds with the RUF, selling their arms to the rebels for diamonds. With the passing of a few years Executive Outcomes came to be seen in a slightly different light, mainly because of the inefficiency of the UN forces. In May 2000 for example, two articles were published in Time and Newsweek, where the the performance of the company was compared positively to that of the UN. The difference regarding costs was particularly devastating: the mercenary company had cost $1.2 million a month for a more effective service, whereas the miserable performance by the UN forces had swallowed up $47 million a month. Furthermore, surveys among the stricken population revealed that huge numbers wanted the mercenaries to return instead of the corrupt and incompetent peacekeepers. But by that time Executive Outcomes had been disbanded, and was already a part of history.