Apocalypse Now

The man who was "Colonel Kurtz".

In Francis Ford Coppola's film "Apocalypse Now", the CIA sent Captain Willard far over the border from Vietnam to secretly dispatch a highly decorated Special Forces officer. Isolated in the jungle, worshiped by his savage mercenaries as a god, the officer had apparently gone mad; broadcasting obscure speeches from his own radio station he waged a private war of such atavistic cruelty that it proved too much for even his normally not-too-sensitive superiors at the Pentagon. The role that Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" played in the creation of Coppola's Colonel Kurtz is well known, but there are other, more recent references too. The real reason for transplanting the mad Kurtz from the Congo to the no-man's land beyond Vietnam can be found in the CIA's covert operations in Laos and Cambodia. As early as the late 1950s, intensified guerrilla activities had been observed by the

CIA in South Vietnam. Supply routes ran over the border through the remote mountain

regions of Laos and Cambodia, and would later come to be known as the Ho Chi Minh trail.

To get this problem under control it was decided to recruit mercenaries for the war

against communism from amongst the native Hmong hill tribes. It was hoped that they would

be able to not only prevent supplies reaching the Vietcong in South Vietnam, but also stop

the infiltration of Laos and northern Thailand. Since the US wasn't at war with either

Laos or Cambodia, any involvement there had to be kept secret from the public, and for

this purpose all logistics were managed by CIA-owned airline Air America, or one of its

countless subsidiaries. The necessary field work was carried out by a handful of Green

Berets whose existence could always be denied by the US authorities. Their task was to

recruit mercenaries from among the Hmong tribesmen, to train them with the weapons

supplied by Air America, to assign them tactical objectives and to request air support

if needed.

As early as the late 1950s, intensified guerrilla activities had been observed by the

CIA in South Vietnam. Supply routes ran over the border through the remote mountain

regions of Laos and Cambodia, and would later come to be known as the Ho Chi Minh trail.

To get this problem under control it was decided to recruit mercenaries for the war

against communism from amongst the native Hmong hill tribes. It was hoped that they would

be able to not only prevent supplies reaching the Vietcong in South Vietnam, but also stop

the infiltration of Laos and northern Thailand. Since the US wasn't at war with either

Laos or Cambodia, any involvement there had to be kept secret from the public, and for

this purpose all logistics were managed by CIA-owned airline Air America, or one of its

countless subsidiaries. The necessary field work was carried out by a handful of Green

Berets whose existence could always be denied by the US authorities. Their task was to

recruit mercenaries from among the Hmong tribesmen, to train them with the weapons

supplied by Air America, to assign them tactical objectives and to request air support

if needed.

What appealed to foreign powers about the Hmong was their long warrior tradition. In the

last years of the Indochina War the French had formed a small army of Hmong, whom they

called Montagnards (i.e. "mountain people"), which had fought in the Plain of Jars against

the Vietminh. The Hmong were hardy, brave and knew the jungle trails. They were the perfect

soldiers, and one of them was Vang Pao. In 1945 at the age of 13, he started his military

career as a translator for French paratroopers who tried to organise resistance against

the Japanese in the Plain of Jars. He became a lieutenant in the new Laotian army and led

a commando unit in a vain attempt to relieve the encircled French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

By the end of the Indochina War, he was a major in the regular army and also commanded the

self-defense militias of the Hmong in the Plain of Jars.

What appealed to foreign powers about the Hmong was their long warrior tradition. In the

last years of the Indochina War the French had formed a small army of Hmong, whom they

called Montagnards (i.e. "mountain people"), which had fought in the Plain of Jars against

the Vietminh. The Hmong were hardy, brave and knew the jungle trails. They were the perfect

soldiers, and one of them was Vang Pao. In 1945 at the age of 13, he started his military

career as a translator for French paratroopers who tried to organise resistance against

the Japanese in the Plain of Jars. He became a lieutenant in the new Laotian army and led

a commando unit in a vain attempt to relieve the encircled French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

By the end of the Indochina War, he was a major in the regular army and also commanded the

self-defense militias of the Hmong in the Plain of Jars.

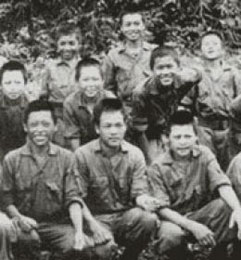

Like all of Laos, the Hmong were dragged into the maelstrom of the conflict between pro-American forces, neutralists and the communist Pathet Lao. Vang Pao and the Hmong chose the side of the Americans. The CIA recruited thousands of these brave jungle warriors, who subsequently defended the north of Laos, rescued downed American pilots and ambushed Vietnamese convoys on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Some teams even crossed the border into China, where they observed military movements or tapped phone lines. But the war imposed an enormous toll on them: facing superior enemy forces, thousands perished in the jungle as they had to abandon more and more villages, retreating further into the mountains.

Air America was dropping mainly rice at this stage as the Hmong became a refugee population,

whose only purpose was to fight and die for the US' secret war. If a village wanted rice it

had to provide warriors. When it tried to escape this cycle, it was denounced to the Pathet

Lao or treated as an enemy. Nevertheless the number of mercenaries dropped and Vang Pao

increasingly recruited from among other mountain tribes. In 1971, at the peak of the fighting,

the Hmong accounted for about 40% of his troops and many of these were child soldiers. Even

in 1968 a CIA adviser had admitted: "A short time ago we rounded up 300 fresh recruits. Thirty

percent were 14 years old or less, and ten of them were only ten years old. Another 30 percent

were 15 and 16. The remaining 40 percent were 35 or over. Where were the ones in between? I'll

tell you, they're all dead...and in a few weeks, 90 percent of [the new recruits] will be

dead."

Air America was dropping mainly rice at this stage as the Hmong became a refugee population,

whose only purpose was to fight and die for the US' secret war. If a village wanted rice it

had to provide warriors. When it tried to escape this cycle, it was denounced to the Pathet

Lao or treated as an enemy. Nevertheless the number of mercenaries dropped and Vang Pao

increasingly recruited from among other mountain tribes. In 1971, at the peak of the fighting,

the Hmong accounted for about 40% of his troops and many of these were child soldiers. Even

in 1968 a CIA adviser had admitted: "A short time ago we rounded up 300 fresh recruits. Thirty

percent were 14 years old or less, and ten of them were only ten years old. Another 30 percent

were 15 and 16. The remaining 40 percent were 35 or over. Where were the ones in between? I'll

tell you, they're all dead...and in a few weeks, 90 percent of [the new recruits] will be

dead."

Since the CIA never had enough staff on hand to take care of every detail, it put local warriors in charge of each tribe. These men organised the recruitment of new soldiers, led them into battle and paid them with American money. Over the years some of them evolved under such conditions into powerful warlords who pursued their own interests above all else, embezzling a portion of the pay and weapons, as mercenary leaders had done throughout history. But the really big money was made with the heroin trade.

The Hmong had traditionally grown opium, but under the guidance of the warlords and with the infrastructure and protection of the CIA, business soared to unprecedented heights. Vang Pao and other Laotian generals made use of their own aircraft which they had at their command, or ordered the product to be transported directly by Air America to the markets in Saigon, Bangkok and Manila. The fact that heroin contributed significantly to the disintegration of the US military force in South Vietnam was considered acceptable by the CIA. One of the American advisers was a certain Edgar Buell who had volunteered, as a former farmer and a good Christian, to come to Laos to organise humanitarian aid for the Hmong refugees. Soon he put his agricultural skills to use, improving Hmong techniques for planting and cultivating opium, allowing them to increase their harvest enormously. Buell warned them: "If you're gonna grow it, grow it good, but don't let anybody smoke the stuff."

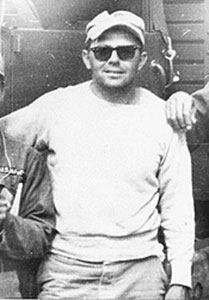

If morality is the first victim of every war, in Laos some records were broken in this matter. One still wonders what kind of crusaders went there to fight a war for America, supporting the drug trade, banding with corrupt and criminal warlords, leading children to the slaughter. The most famous among them, who some experts point to as the "real" Colonel Kurtz, was the CIA operative Anthony Poshepny, Tony Poe for short, but also known as agent Upin or Pat Gibbs. Poe had already fought in the US Marine Corps in World War II, and later joined the CIA and served in Korea and in several secret US wars.

In the 1950s he recruited members of the Tibetan Khamba people in the north-east of India, trained them at Camp Hale in Colorado and accompanied them into Tibet to fight for the Dalai Lama against the Chinese. Poe was one of the few who survived this mission. He also worked in Sumatra organising a revolt against the Indonesian government. Later he trained native soldiers in Cambodia to fight against the government of Prince Sihanouk, and in the early 1960s he was sent as chief adviser to General Vang Pao in Laos to train the Hmong hill tribes.

Poe had strict orders to take care of organisation and logistics only, and to stay out of combat. However he was far away from any direct supervision and after some time strange rumors began to reach his superiors, stories relating bloody reprisals and atrocities. It came to light that he would pay his men 500 Kip ($1) for an enemy's ear, and that when they had brought him too many ears of doubtful origin he raised the price to 5,000 Kip for a head still wearing a Pathet Lao cap. The ears he hung like garlands from his porch roof, while the heads of his more important enemies he preserved with alcohol in jars; the rest were dropped behind enemy lines.

The apex of his defiance of official instructions came when he married a Hmong princess. This

was against all protocol and a step too far for his CIA superiors at the embassy in Vientiane.

They sent men to bring Poe under control again, but this proved easier said then done. Poe had

established himself in a village near the Chinese border where he lived according to his own

rules, and to deal with this kind of life by mid-morning each day he had swigged at least a

quart of whiskey. Sometimes he went off with his Hmong warriors crusading in his own personal

war, even crossing the border into China if it was deemed necessary. For his warriors he was

a godlike figure, who could order rice and weapons to drop from the sky, and if stronger enemy

positions were identified he called napalm to rain on them.

The apex of his defiance of official instructions came when he married a Hmong princess. This

was against all protocol and a step too far for his CIA superiors at the embassy in Vientiane.

They sent men to bring Poe under control again, but this proved easier said then done. Poe had

established himself in a village near the Chinese border where he lived according to his own

rules, and to deal with this kind of life by mid-morning each day he had swigged at least a

quart of whiskey. Sometimes he went off with his Hmong warriors crusading in his own personal

war, even crossing the border into China if it was deemed necessary. For his warriors he was

a godlike figure, who could order rice and weapons to drop from the sky, and if stronger enemy

positions were identified he called napalm to rain on them.

What the office-bound officials and pale theoreticians at the embassy wanted mattered very little to him. He took one emissary of the CIA on a flight across the border into China, threatening him to throw him out of the helicopter. Sometimes when he was totally drunk he swore on his radio station at the CIA and the American ambassador. To help his superiors understand what kind of war he was fighting out there, he sent some of his reports with severed ears attached. Thereafter the CIA resolved to get rid of him by any means, sending two assassins, first a Laotian, then an American. Poe survived both attacks but lost two fingers defusing a booby trap set by the American.

As the Vietnam War escalated, the Americans began to intervene directly in Cambodia, and Poe fell into oblivion. He stayed until March 1973, when he had to flee from the forces of the Pathet Lao. Nothing remains of his base; one day after he left he had it bombed with napalm. After the US ended their support for Laos completely and started to withdraw their troops from Southeast Asia, the Hmong were left to fend for themselves and flee from the oncoming superior forces.

Many of them went to the United States; Vang Pao settled in Fresno as a wealthy businessman.

Though rumors persisted of ongoing drug deals, officially the general devoted himself entirely

to the political struggle for the freedom of his people. Some Hmong, however, remained in

refugee camps in northeastern Thailand. It seems that Poe at first preferred their company to

the prospect of returning home. Apparently, however, he had difficulties adjusting to a peaceful

civilian life, and had repeated run-ins with the police due to violence. At first, the Thai

authorities indulged him on account of his merits in the fight against communism, but when his

behaviour failed to improve, they put him on a plane in Bangkok and sent him home to the States.

There he settled in San Francisco. Journalists who later came looking there for the "real Colonel

Kurtz" were sorely disappointed. Instead they found an old man parading his medals, rambling of

lopped-off ears and heads and complaining bitterly that he had never been invited to veterans'

meetings.

Many of them went to the United States; Vang Pao settled in Fresno as a wealthy businessman.

Though rumors persisted of ongoing drug deals, officially the general devoted himself entirely

to the political struggle for the freedom of his people. Some Hmong, however, remained in

refugee camps in northeastern Thailand. It seems that Poe at first preferred their company to

the prospect of returning home. Apparently, however, he had difficulties adjusting to a peaceful

civilian life, and had repeated run-ins with the police due to violence. At first, the Thai

authorities indulged him on account of his merits in the fight against communism, but when his

behaviour failed to improve, they put him on a plane in Bangkok and sent him home to the States.

There he settled in San Francisco. Journalists who later came looking there for the "real Colonel

Kurtz" were sorely disappointed. Instead they found an old man parading his medals, rambling of

lopped-off ears and heads and complaining bitterly that he had never been invited to veterans'

meetings.